In Miami, it’s the year of the Chinese artist

Shows at UM’s Lowe and FIU’s Frost museums are the latest episodes in Miami’s ongoing affair with Asian art.

BY GEORGE FISHMAN

SPECIAL TO THE MIAMI HERALD

08/02/14

Audio

Hear Brian Dursum on copying and attributions.

bitly.com/BrianDursumAttribution

Hear Brian Dursum on post-Qing developments.

bitly.com/BrianDursumModernChina

Hear Carol Damian on meeting Simon Ma.

Hear Carol Damian on FIU’s China connection.

Chinese artist-activist-celebrity Ai Weiwei set off fireworks during the Pérez Art Museum Miami’s December inauguration with his powerhouse solo exhibition. Then the Rubell Family Collection mounted its probing contemporary survey, 28 Chinese, which just wrapped up.

Now Miami audiences can feast on four more exhibitions of art from China. Three successive solo shows at Florida International University’s Frost Museum feature renowned contemporary artists, while China’s Last Empire, which opened in July at the University of Miami’s Lowe Art Museum, provides context for understanding China’s emergence as a global art force.

Visitors can use the Lowe exhibition for grounding in China’s visual arts heritage, then travel to the Frost to find both continuity and disruption of those traditions.

The Lowe’s Brian Dursum isn’t greedy for glory. Celebrating a 40-year university museum career — he has been director and chief curator since 2009 — Dursum graciously invited several colleagues to play a role in his final exhibition before retiring. China’s Last Empire: The Art and Culture of the Qing Dynasty benefits from abundant scholarship, which Dursum will continue independently in retirement.

Dynastic succession in China has sometimes been violent, wrought by invaders from the north who bribed their way over the Great Wall. But the final Imperial dynasty — the Qing — which extended from the mid-1600s into the 20th century, maintained most of Chinese society’s most important traditions.

While the Qing originated in Manchuria, “They adopted the way the Chinese would rule, the way the Chinese thought,” Dursum says. The Lowe’s exhibition reveals that continuity through its display of clothing, ceramics, tomb rubbings, vases and document boxes, as well as what Westerners segregate as “fine art” — drawings, paintings and sculpture — and, more recently, photography.

The exhibition’s thematic modules provide insight into how society was organized according to Confucian principles of altruism, fairness, scholarship and hierarchical relationships of duty. It was — at least in principle — a meritocracy. Advancement was regulated by an imperial examination system. China’s all-encompassing bureaucracy was governed by men of the literati class who, besides their administrative duties, devoted themselves to cultural pursuits.

“Painting and calligraphy were vital to the literati,” Dursum says. “Not all of them turned out to be great painters, but most of them painted. And most of them did poetry, and their poetry and their calligraphy and their painting oftentimes would merge and become one.”

Reverence for nature, intricate patterning, splendid virtuosic brushwork and pairings of drama and stillness are among the values expressed in 268 years of Qing paintings, ceramics, sculpture and fabrics. They further draw on 3,000 years of Chinese artistic tradition.

Greeting Lowe Museum visitors are select pieces that gently lead back to a serene world. Poets Gathering on a Spring Night in the Peach and Pear Garden is a faithful copy of a vertical landscape by the illustrious mid-16th century painter Qiu Ying, who in turn imitated artists from centuries earlier. It’s initially surprising to see so many copies and unidentified artists, but Dursum explains that, unlike in Europe, “The Chinese idea is not forgery so much; it really is learning from the past.” By copying, they preserve works otherwise lost — for posterity. This painting also embodies the cultural value of diminutive human figures dwarfed and inspired by nature.

The emperor was considered divinely appointed. Like his elevated subjects, he was also expected to excel in painting, poetry and calligraphy. The exclusivity of imperial status radiates through clothing, porcelain vessels and ceremonial objects, created by and for the royal court. For example, only the emperor, empress or empress dowager were allowed to wear yellow robes bearing the five-toed dragon.

Except for religious figures and objects, the human form literally and figuratively assumes modest proportions. Such Daoist characters as Shoki and Oni provide a glimpse into belief systems akin to the Santeria and Voudou figures presented in other recent Miami exhibitions.

Two arresting funerary portraits convey the culture’s reverence for esteemed ancestors — and the perceived importance of accurate portrayals. Getting the whiskers of Uncle’s mustache wrong might jeopardize his family’s afterlife status!

Calligraphy is everywhere. It embodies the vital connection between words and the visual arts. The symbol-based written language of China reveals the expressive sensitivity of the practitioner, just as do the brush strokes depicting a horse’s noble head, a plunging waterfall or a plum blossom. Pear Blossoms and White Swallows contains a veritable appendix of seals and commentaries on its artistry and authenticity, solicited by its avid collector in 1823.

The show traces exchanges between China, Japan and Korea and, more dramatically, Europe. French and Italian perspectives on Chinese life are intriguingly represented in the Interactions section. China’s material culture and stable governance were admired by its neighbors in Korea and Japan and, once trade developed in the 1500s, by Europeans.

Chinoiserie references the influence of Chinese motifs and methods on fabric and ceramic production in Europe as well as Chinese wares produced for the European trade. Artisans’ readiness to produce work for export is exemplified by a barrel-shaped box bearing an eagle emblem with red and white stripes made for the United States’ 1876 centenary. Wares for Turkish export bear Ottoman motifs.

Little has changed today. Ironically, it was the imbalance of trade — among other factors — that led, through the Opium Wars, to the decline and collapse of imperial China and on to successive upheavals.

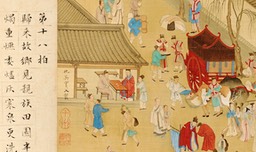

Outsiders’ images of China are intriguing. A Latin-inscribed watercolor from around 1700 depicts Emperor Kangxi’s swarming New Year’s pageant. Italian Jesuit missionary, Giuseppe Castiglione contemporaneously painted 10 prized imperial dogs in a style that marries east and west. The paintings were copied in porcelain dishes. French artist Auguste Borget presents genre studies of the mid-19th century landscape, architecture and working people. Finally, early 20th-century photos of the “last first family” of the Qing empire provide poignancy and immediacy to people moving from an epoch in eclipse to another fraught with uncertainty.

Since the era of the Maoist cultural revolution with its populist, propagandist murals and posters, China has developed both contemporary-oriented art schools and a booming marketplace for eastern and western art. The Frost, with ongoing funding from Taiwanese-American benefactor, Jane Hsiao of Opko Health, is showcasing three contemporary “giants,” representing both continuity and change. Prior exhibitions have presented such contrasting imagery as a National Geographic photo-style documentation of Taiwan and mainland Chinese artists’ caustic, ironic engagement with American brands, logos and other pop-culture imagery.

The current exhibition, Simon Ma’s Heart-Water-Ink, is a tribute to the late painter Xu Beihong, whom the 40-year-old Ma greatly admires. Born in 1895, Xu trained in China and Japan, then studied throughout Europe during the fertile 1920s. He returned and became an influential teacher, bridging east and west.

A generation later, Ma studied in Hong Kong (calligraphy/painting) and London (architecture). His flamboyant style in various art modalities, product design and branding (somewhat akin to Miami’s Romero Britto) have catapulted him into international stature, evidenced by a satellite exhibition of his designs held during the 2013 Venice Biennale.

During Hong Kong’s Art Asia 2012, Frost director Carol Damian saw Ma in a painting demo; musician Julian Lennon was photographing him. Damian immediately recognized Ma’s talent and charisma.

“There’s no doubt this man is a showman, and he always has people around him,” she says. His deft integration of divergent styles and mediums was also intriguing. She offered him an exhibition “sometime in the future.”

That future was soon set as summer 2014. This is the Chinese Year of the Horse, and “it was very important for him to be able to showcase his favorite subject, which is the horse,” Damian says.

Ma means horse in Chinese, so the association works on several levels. Horses were among the favored motifs of Xu Beihong, and horses are ubiquitous in Ma’s show, which includes sculptural chairs, a 3D video, a stampede of toy-size horses, a horse-dragon hybrid and paintings in various styles and mediums, including graffiti and Frankenthaler-like canvases. In Ma’s hands, the imperial dragon, seen earlier at the Lowe, reappears, now in the form of a hybrid creature with a horse’s features.

Blackmer, a towering wall-mounted horse silhouette, is composed of several dozen paper squares. Each bears a fanciful multicolored pictographic composition that Chinese readers can interpret, and each conveys an aspect of the horse, Damian says.

Ma’s talent is most striking in his abstracted gestural paintings Brush Soul, Cliff 2 and Zoulou. Their rhythms and compositional integrity show spontaneity and playfulness, rather than self-conscious pursuit of style. “They might appear to be Chinese ink brush paintings, calligraphy, markings, but when you get up close, you realize they’re not,” Damian says. “He invents his own language, his own way of symbolizing, which is very important.”

To that end, Ma liberates traditional Chinese calligraphic markings from their linguistic duty, and they become fanciful landscapes or imaginary symbols.

During the run of his show, Ma will make a yet-unscheduled visit and demonstrate his painting technique to the public.

In November, Wang Qingsong’s exhibition of elaborately staged photography arrives at the Frost. “He’s interested in change and the abruptness of change,” Damian says. “They just knock down blocks of traditional homes and put up a skyscraper. And what happens to the people?” Damian asks. “You might see in one frame a statue of a Buddha or a dancer in traditional clothing, and then next to it a picture of a kid smoking a cigarette.”

Giant in scale, Wang’s photographs are frequently populated by scores of orchestrated figures in bizarre settings. He pillories the rampant consumerism and dislocations of contemporary China with virulent humor.

Xu Bing is a renowned printmaker and book artist, currently best known for his gigantic phoenix sculptures, fashioned of recycled construction debris, that hang in Saint John the Divine cathedral in New York. At the Frost in February 2015, he will install Book From the Sky, a monumental scroll that will hang across the gallery. “It’s executed in an invented language,” Damian says, “but the artist will teach how to understand it.

“It’s going to look like a beautiful traditional Chinese scroll, and then on the bottom are going to be pages — scrolls again — from a book. So, it’s like the book from the sky, and each one of these pages from the book is going to be translatable because he gives you the key.

“It’s taking the traditions of calligraphy and the chop mark and bringing it into a whole new dimension of interest in education,” Damian says. “He’s talking about the significance of poetry and reading and language, but he’s talking about the language for a new generation.”

IF YOU GO

What: ‘The Last Empire: The Art and Culture of the Qing Dynasty’

When: Through October 19

Where: The Lowe Art Museum, University of Miami, 1301 Stanford Drive, Coral Gables

Info: 305-284-3535; http://lowemuseum.org

and

What: ‘Simon Ma: Heart-Water-Ink World Tour Exhibition 2014 — Tribute to Mr. Xu Beihong’

When: Through Oct. 19

Where: The Patricia & Phillip Frost Art Museum, Florida International University,

10975 SW 17th St., Miami

INFO: 305-348-2890; http://thefrost.fiu.edu/

FYI: Free

Several other exhibitions will also be on view at both venues.